Imagine a doctor says “The patient likely has pneumonia” versus “The patient has pneumonia.” That single word changes everything. The first statement hedges the diagnosis, expressing uncertainty that could affect treatment decisions. The second makes a definitive claim.

This is what hedge detection is about - automatically identifying these linguistic markers of uncertainty in text. In our recent work with Rivka Levitan, we tackled this problem on the CoNLL-2010 Wikipedia dataset and beat the previous benchmark. Here’s what worked.

Why this matters

Understanding certainty levels in language matters in high-stakes fields. In medicine, distinguishing “the tumor appears malignant” from “the tumor is malignant” affects patient care. In finance, “earnings may decline” versus “earnings will decline” drives investment decisions. In scientific literature, knowing which claims are confident versus speculative helps researchers assess evidence.

The challenge is that hedges come in many forms. Modal verbs like “might” and “could” are obvious. But hedging also appears in phrases like “it is possible that” or “there is evidence to suggest.” Sometimes the same word hedges in one context but not another - “you may enter” grants permission while “this may be correct” expresses doubt.

The dataset

We worked with the CoNLL-2010 shared task Wikipedia corpus. It contains 11,110 training sentences and 9,634 evaluation sentences, with annotations marking hedge cues. The mean sentence length is 22.5 words. The data is imbalanced - 77.26% of sentences are certain versus 22.74% uncertain - which makes this harder than it looks. We limited sentences to 64 words and used spaCy for part-of-speech tagging.

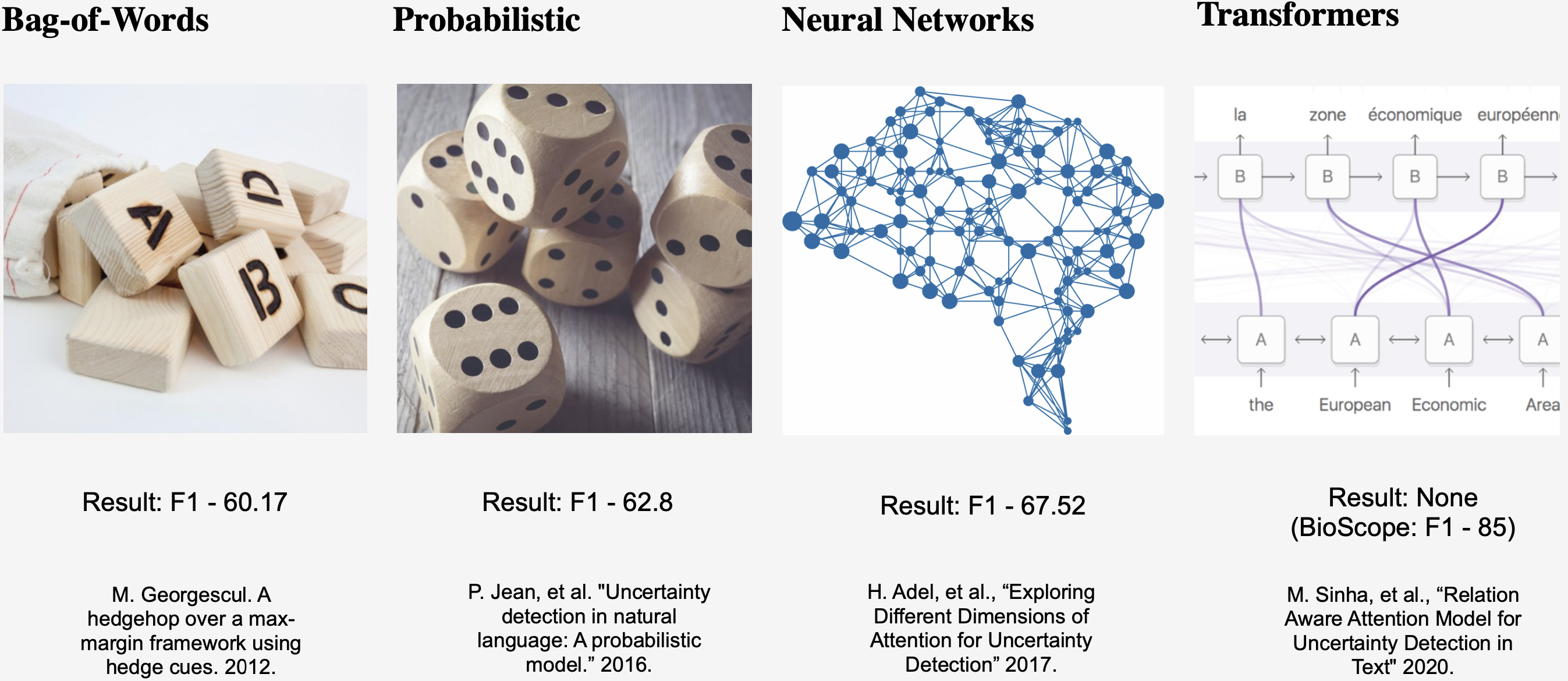

After setting aside a development set, we trained on 9,999 samples. Because of the class imbalance, we applied class weighting during training and measured performance with F1 score rather than accuracy. The previous best result on this dataset was 67.52 F1.

Our approach

We tested multiple neural network architectures: CNNs, GRUs, LSTMs, and Transformers. We also added attention mechanisms to see if they helped. All models used the same hyperparameters - 64 RNN hidden units, batch size of 64, and 0.5 dropout rate at each layer. Each architecture had two layers with a dense output layer containing a single neuron for binary classification.

For word representations, we tried several pre-trained embeddings:

- FastText 2M vectors (300d)

- GloVe 6B vectors (300d)

- GoogleNews Word2Vec (300d)

- Custom Wikipedia 1GB embeddings (256d, trained ourselves)

The key insight was that grammatical structure matters for hedge detection. Part-of-speech tags capture patterns like modal verbs and specific verb forms that consistently signal uncertainty. We encoded POS tags as 8-dimensional embeddings that the model learned during training.

We explored two ways to incorporate POS information:

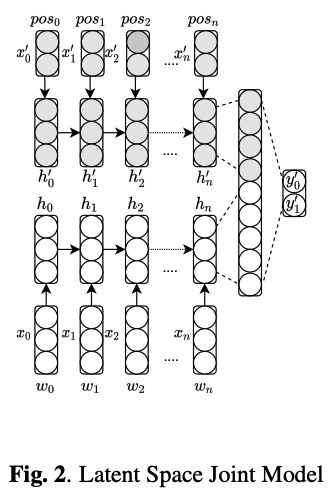

First, concatenating POS embeddings directly with word embeddings at the input layer (joint input).

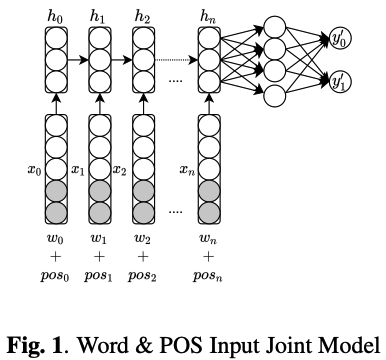

Second, running separate networks for words and POS tags, then merging their hidden representations at the final layer before classification (joint latent space). This lets each network specialize - one learns semantic patterns, the other learns grammatical structure.

We trained each model until development error stabilized, then sampled 10 additional iterations and reported mean scores to ensure robustness.

Results

Baseline word-only models

Among single-modality models using only words, GRUs performed best with a mean F1 of 63.78, followed by LSTMs at 63.47. Adding attention to GRUs produced 63.62 F1 - not a consistent improvement.

Across embeddings, FastText performed best at 63.57 F1, followed by GloVe at 63.12 F1. Custom Wikipedia embeddings came in at 61.99 F1, while GoogleNews lagged at 60.34 F1.

POS-only models

To test whether grammatical structure alone contains useful signal, we trained models using only POS tags. An LSTM with attention achieved 48.9 F1 using just grammatical patterns. This is well above random and demonstrates that hedging has clear grammatical signatures - certain POS sequences consistently indicate uncertainty.

Joint models

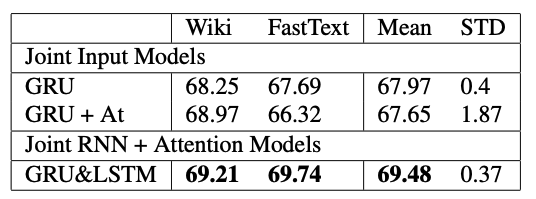

Combining words and POS information produced substantial gains. The joint input approach (concatenating word and POS embeddings) achieved 66.08 F1 with a GRU and FastText. The joint latent space approach (separate networks merged late) reached 65.46 F1 with GRU for words and LSTM for POS.

The best joint configuration paired GRU+attention for words with LSTM+attention for POS tags, hitting 69.48 F1 on the development set and 69.74 F1 on the final evaluation.

Best overall result

Surprisingly, our highest score came from a relatively simple GRU using custom Wikipedia embeddings - 70.24 F1. This beat the previous benchmark of 67.52 F1 and even outperformed our more complex joint models.

Three findings stood out:

First, simpler architectures can win. The basic GRU outperformed more complex models when paired with domain-specific embeddings. This matters for deployment where computational efficiency counts.

Second, part-of-speech tags carry substantial predictive power. The fact that a POS-only model achieved nearly 49 F1 shows that hedging has clear grammatical patterns. Modal verbs, certain adverb classes, and specific verb forms consistently mark uncertainty.

Third, domain-specific embeddings matter. While FastText performed well among general embeddings, custom Wikipedia embeddings provided the best overall result. Wikipedia’s encyclopedic style, with its careful hedging around uncertain claims, creates ideal training data for this task.

What we learned

The joint modeling approach works because it allows specialization. The word network learns which lexical items signal hedging. The POS network learns which grammatical constructions signal hedging. Combining both captures the full picture.

Domain-specific embeddings matter more than we expected. While GoogleNews Word2Vec contains more diverse language, Wikipedia embeddings better represent the kinds of hedging we’re trying to detect.

Architecture complexity doesn’t always help. Our best model was a straightforward GRU. Attention mechanisms and transformers didn’t provide consistent improvements across different configurations.

Applications

Automated hedge detection has immediate uses across several domains. In scientific literature mining, it helps identify which claims are presented confidently versus speculatively. In fact-checking systems, understanding certainty levels improves accuracy. In medical NLP, distinguishing definitive diagnoses from tentative assessments in clinical notes could improve patient care. In financial analysis, detecting uncertainty in earnings reports and analyst predictions aids decision-making.

Related work

Hedge detection builds on decades of computational linguistics research, from early rule-based approaches to modern neural methods. The CoNLL-2010 shared task established benchmark datasets that enabled direct comparisons across different approaches.

Our work shows that combining neural networks with linguistic features remains competitive even as language models grow larger. The advantage is that our approach requires no manual feature engineering beyond POS tagging, which spaCy handles automatically with high accuracy.

Looking ahead

Several questions remain. How well do models trained on Wikipedia generalize to scientific papers, news articles, or social media? Different domains use hedging differently. Can we move beyond binary classification to measure degrees of certainty? Do modern large language models benefit from explicit hedge detection modules, or do they learn this implicitly?

Cross-domain generalization is particularly interesting. Wikipedia hedging might look different from academic hedging or journalistic hedging. Testing transfer learning across these domains would clarify how robust these models are.

Multilingual hedge detection is another open area. Different languages express uncertainty through different grammatical mechanisms. Whether this approach generalizes across languages is an empirical question.

Wrapping up

Understanding not just what text says but how confidently it says it is fundamental to language comprehension. Our results show that neural networks can learn to detect hedging effectively when combined with grammatical information, achieving new state-of-the-art performance on standard benchmarks.

For fields where distinguishing facts from speculation matters, automated hedge detection is more than an academic exercise. The combination of neural pattern recognition with linguistic structure provides a practical approach to this subtle but important NLP task.

Paper: Katerenchuk, D., & Levitan, R. (2024). “You should probably read this”: Hedge Detection in Text. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.13319

Code and Models: Available upon request for research purposes.